|

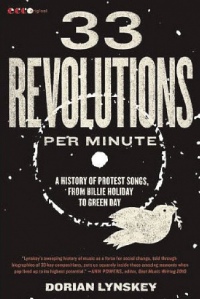

33 Revolutions Per Minute

- A History of Protest Songs, From Billie Holiday to Green Day

reviewed by Alan Zisman (c) 2011

First

published in Columbia

Journal September 2011

33

Revolutions Per Minute

- A History of Protest

Songs, From Billie Holiday to Green Day

by Dorian Lynskey

2011, Ecco Publisher

ISBN-13: 978-0061670152

688 pages, $19.99

There’s a pop-culture myth about protest songs - perhaps

related to the myth that all the pop-culture that matters rose and fell

with the baby boomer generation. In that mythologized story, protest

songs started with Woody Guthrie, continued with Pete Seeger and the

Weavers, were driven underground by McCarthyism, re-emerged in

Greenwich Village with Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, and the rest, were sung at

civil rights and anti-Vietnam War rallies, and then faded away along

with the counter-culture and protest movements in general. There’s a pop-culture myth about protest songs - perhaps

related to the myth that all the pop-culture that matters rose and fell

with the baby boomer generation. In that mythologized story, protest

songs started with Woody Guthrie, continued with Pete Seeger and the

Weavers, were driven underground by McCarthyism, re-emerged in

Greenwich Village with Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, and the rest, were sung at

civil rights and anti-Vietnam War rallies, and then faded away along

with the counter-culture and protest movements in general.

Dorian Lynskey is a music reviewer for the UK’s Guardian newspaper. As

the title of 33 Revolutions Per Minute - A History of Protest Songs,

From Billie Holiday to Green Day suggests, he’s written a history of

protest songs, structured as 33 chapters, one for each of 33 songs.

Also, as the subtitle points out, he extends the canon of protest songs

beyond the Dylan/Baez genre; while including chapters on Woody Guthrie

and his descend introduced Abel Meeropol’s ‘Strange Fruit’ to the

audience of New York’s Café Society.

Lynskey recognizes that there were protest songs prior to ‘Strange

Fruit’ – and even includes a two-page appendix on protest songs prior

to 1900. However, he suggests that earlier protest songs were outside

the pop song mainstream - “They were designed for specific audiences —

picket lines, folk schools, party meetings.”

Protest songs, however, even the 33 songs that Lynskey selects as key,

often fit at best uneasily within the limitations of pop music. Some of

his songs made it onto the ‘charts’ – Stevie Wonder’s ‘Living for the

City’ or Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s ‘Two Tribes’, for example. Others

– ‘We Shall Overcome’, for instance – had a life of their own, becoming

widely known independent of pop music marketing.

Lynskey understands the problems that can occur when songs with a

message are performed in a pop music context – the irony of the

popularity as a right-wing anthem of Bruce Springsteen’s ‘Born in the

USA’ is commented on.

Some of the artists getting a chapter, such as the Dead Kennedys

(represented by ‘Holiday in Cambodia’) or the British band Crass (with

‘How Does It Feel’) would probably like to think of themselves as

anti-pop.

While each chapter refers to a particular artist and song, Lynskey does

a good job of building context – giving both the story of the band or

singer, of the writing or recording of the song, and the broader

political and cultural context. He often goes into detail about other

artists, as well.

So, while Phil Ochs doesn’t get a chapter of his own, he plays a role

in the chapters on Dylan (‘Masters of War’), Country Joe and the Fish

(‘I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag’) and Victor Jara (‘Manifesto’).

He also does a good job with music post-1975; punk and reggae (of

course), but even noting the rebellious streak in the much-maligned

disco, with a chapter subtitled ‘Gay Pride and the Hidden Politics of

Disco’. He notes the role that songs like the Special-AKA’s ‘Free

Nelson Mandela’ played in the anti-apartheid movement, and with seven

chapters dated from 1989 to 2008 helps show that even during this

period, there were undercurrents of protest, with music ranging from

Public Enemy to Rage Against the Machine, to Steve Earle.

He does a less good job in some other areas, though. Inevitably, the

book is (nearly) limited to the Anglo-American music scene, though

three international chapters are included on Chile’s Victor Jara,

Nigeria’s Fela Kuti, and Jamaica’s Max Romeo. As with the other

chapters, they go beyond the single musicians and songs.

Women are nearly invisible, however. Yes, the book opens with Billie

Holiday. After that, we get Nina Simone (with ‘Mississippi Goddam’).

Then no one until 1993’s Riot Grrrl movement, represented by Huggy

Bear’s ‘Her Jazz’. The Dixie Chicks get mentioned in the context of

Natalie Maines’ 2003 comments about George Bush, but they’re just an

aside in a chapter based around Steve Earle’s ‘John Walker’s Blues’

(subtitled ‘Saying the Unsayable After 9/11’).

(I suppose Lynskey would consider the music of self-identified

feminists like Holly Near as ‘designed for special audiences’).

In an epilogue, Lynskey notes that the best-selling song in the UK over

Christmas 2009 was Rage Against the Machine’s angry ‘Killing in the

Name’. But he points out that this happened as the result of a

grassroots movement to prevent the winner of TV show ‘The X-Factor’

from being the Christmas top of the pops. “The state of political

music”, he suggests: “a protest song can only succeed on a grand scale

if it’s turned into a joke”.

He is pessimistic about the future of protest songs: “The failure of

protest songs to catch light during the Bush years leaves one wondering

what it would take to spark a genuine resurgence”. He suggests that

this is a reflection in a broader “loss of faith in ideology and a

fading belief in what we might call heroes”.

(Or as if what Bob Dylan famously suggested (in a more innocent age) –

‘Don’t follow leaders, watch the parking meters’ has come to pass).

In the end, Lynskey tells us: “To create a successful protest song in

the 21st century is a daunting challenge, but the alternative, for any

musician with strong political convictions, is paralysis and gloom…. To

take on politics in music is always a leap of faith…. It falls to

musicians to continue to make those attempts; whether they succeed or

note depends on the rest of us”.

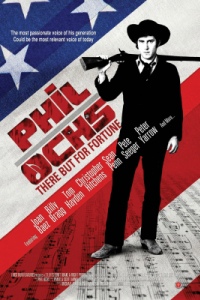

Phil Ochs: There But for Fortune Phil Ochs: There But for Fortune

written and directed by Kenneth Bowser

released by First Run Features

2011, 98 minutes long

Phil Ochs didn’t rate a chapter in Dorian Lynskey’s 33 Revolutions Per

Minute – his 1967 album ‘Pleasures of the Harbor’ made it to #168 on

the Billboard charts. he is the subject of the 2011 documentary: Phil

Ochs: There But For Fortune, which was screened in August by the

Pacific Cinematheque.

Written and directed by Kenneth Bowser, the 98 minute film looks at the

life, music, and times of Ochs, with numerous interviews with

contemporaries from Joan Baez to Tom Hayden, family members including

Ochs’ brother, sister, wife, and daughter, as well as people influenced

by his music, such as Billy Bragg and Sean Penn. Bob Dylan (who does

get a chapter in Lynskey’s book) apparently refused to be interviewed.

(Apparently, Ochs often felt like he was competing with Dylan; Dylan

never compared himself to Ochs).

News clips are effectively used to place Ochs and his music in the

context of the civil rights and anti-war movements of the 1960s.

While Ochs tried to move his music beyond the “All the News That’s Fit

to Sing” topical songs of his early albums, he is most remembered for

his series of protest songs from the early to mid 60s, reflecting his

sense that the US was failing to live up to promises of justice and

equality.

The documentary shows how Ochs, with a family history of

manic-depression and a tendency towards alcoholism, was unable to move

beyond the movements of the 1960s. As the anti-war movement wound down,

his 1970s centered around the 1973 coup in Chile (and the murder of

Chilean political singer Victor Jara), a trip to African – where his

little-heard recordings with African musicians pre-figured similar

recordings by Peter Gabriel and Paul Simon – that resulted in a mugging

that damaged his vocal chords, and finally the end to the Vietnam War.

Less than a year after the fall of Saigon, Phil Ochs hung himself in

his sister’s house. He was 35.

|