Open Road differentiated itself from

the mainstream and “sectarian leftists organs” in that its reportage

sought to convey “anti-authoritarian trends and developments wherever

they may occur, and to push no organization other than those which are

created and sustained by ordinary people in the heat of struggle.”

(Issue 2, page 3).

On the origin of Open Road:

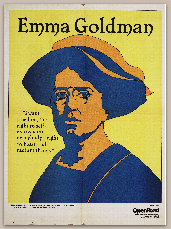

At an early meeting to choose a name, Socialism with Freedom was proposed, but instead the collective wisely went with The Open Road, the name Emma Goldman had originally planned to call her Mother Earth magazine. The Open Road collective had considerable experience in the underground press and other publications, and we set out to produce a journal that looked as good and read as well as any of the popular rock 'n' roll magazines of the day. We also had years of experience organizing street protests and cultural events, so the OR statement of purpose that appeared in issue No. 1 ("Still Crazy After All These Years") was referring to ourselves as well as to our readers when it said: "In the last decade … in every arena of struggle people are rejecting sectarian and authoritarian methods of organization in favour of full rank-and-file participation and direction." Most of the core group that produced issue No. 1 had been active in Vancouver's Youth International Party (the Yippies). Alongside our serious political goals, there was a playfulness to OR, as exemplified by its often humorous headlines and issue No. 1's comic-book cover

Once No. 1 was completed we did a mass mailing, then waited anxiously for the response. (Much of this mail-out was made possible by friends at the New York-based newspaper Yipster Times, who gave us their substantial mailing list.) The letters came pouring in. One from an Alabama activist, Michael Littlefarb, was typical: "I can't remember the last time I got so excited. … spoke to me at a deeper level than anything I have seen since the Sixties." Buoyed by the gratifying response, we moved on to issue No. 2 and 3 and… The original collective would produce The Open Road for its first few years, then other collectives would continue until it finally ceased publication in 1990.

-- David Spaner, March 2015

On the importance of Open Road:

As David Spaner’s comments illustrate, the origins of Open Road offer us a pathway in to the politically transformative years of the 1970s, and beyond. In an immediate sense, the existence of the paper can draw our attention towards a global shift that took place within political and cultural character of the New Left. Like other activists at the time, the Open Road collective was deeply motivated by the New Left’s militancy and its emphasis on community organizing, anti-capitalism, and anti-imperialism, as well as its quest for social and personal liberation. Nevertheless, as Spanner notes, the political and cultural influence of Marxism-Leninism was also limiting for some activists. As a result, these radicals turned to anarchism as an alternate form of revolutionary socialism. In this search, anarchists in the 1970s were part of a much older pattern of leftist organizing that had sought to develop alternatives to state socialism since the 19th century.

In Vancouver, as in many other places, these political and cultural motivations produced a resurging pattern of anarchist activism beginning in the 1960s and 1970s. Locally, the publishing of Open Road helped to catalyze the promotion of new anarchist projects, including reading groups, agitprop initiatives, periodicals, and collectives that sought to bring anarchist politics into direct conversation with the broader radical traditions of the time. But these transformations were also global. If you turn to the pages of Open Road, you will see the geographical diversity of this resurgence in the form of published letters that were sent to the collective from anarchists around the world. In this sense, anarchist politics contributed significantly to the transformation of social movement activism in the decades after the 1960s, both in Vancouver and elsewhere.

This history is particularly relevant because of the strong connections that continue to link the post-1960s and the present. In the span of time between then and now, anarchist politics, culture, and activism have gone through many changes. Nevertheless, if you were to flip through the pages of Open Road you would find a diverse body of opinion on great number of familiar topics: indigenous struggles, gender and sexuality, anti-militarism, technology and the surveillance state, feminism, armed struggle, the politics of organization, environmental activism, workplace struggles and the labour movement, anti-imperialism, popular culture, prison abolition, and many other issues. The interpretation of these issues might seem deeply familiar. They might also seem different in ways that are inspiring, perplexing, infuriating, or downright disturbing. But regardless of whether we see in Open Road continuities with who we are now, or confirmations of what we are not, the very act of exploring will hopefully provide a sense of perspective to those of us who find value in understanding our own identities in relation to those who came before us.

-- Eryk Martin, May 2015

- Video playlist of speakers at the Sept 2021 Hornby Island celebration of Open Road co-founder Bob Sarti

- A Final Curtain Call for Brotha Bob - a poem in memory of Bob Sarti by Ron Sakolsky

- Memory of Open Road co-founder Bob Sarti by John Mackie

- Remembering Robert Sarti - 1943-2020

- Memories of Bob Mercer by Larry Gambone

- Remembering Bob Mercer by David Spaner

- Ken Lester - Cultural Rebel by Dave Lester

- Vancouver Yippies Reunion 2011

Some Links:

- Earth & Fire - In 1972, before there was an Open Road, some folks in Vancouver published Earth & Fire - Here are Issue #1 (April 1972) and Issue #2 (Summer 1972). Large file sizes may take a while to display/download!

- University of Victoria's Anarchist Archives: http://www.uvic.ca/library/featured/collections/anarchist/index.php

- Arm the Spirit collection of anarchist materials--including a range of Direct Action related documents--posed on Issuuu and Scribid: http://issuu.com/randalljaykay https://www.scribd.com/ArmTheSpirit

- Robert Graham's Anarchist Blog

- Vancouver Yippie! and Anarchism

- The Life and times of Anarchy: A Journal of Desire Armed

- List of digitized anarchist periodicals

- All 9 issues of BC's 1983 Solidarity Times

- 6 AFFICHES DU JOURNAL OPEN ROAD